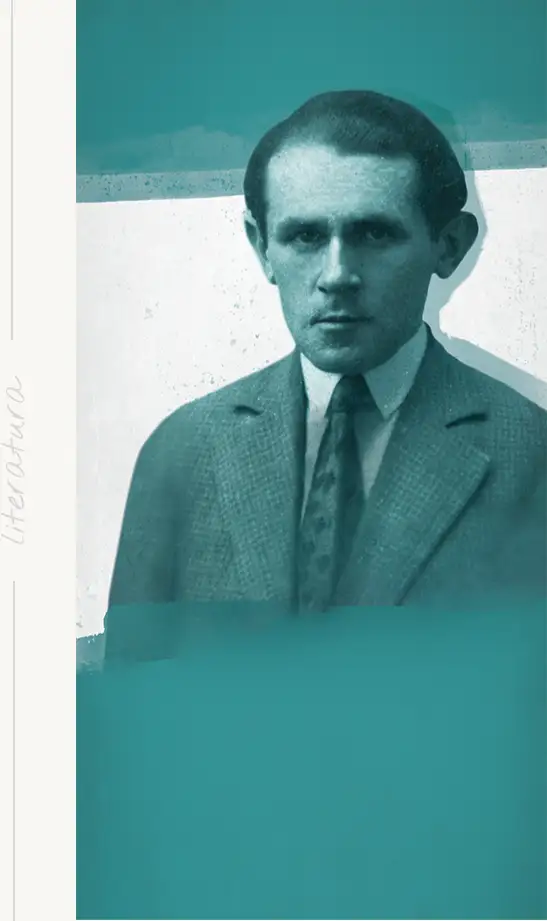

Bruno Shulz

12. 7. 1892, Drohobyč — 19 11. 1942, Drohobyč (dnes Ukrajina))

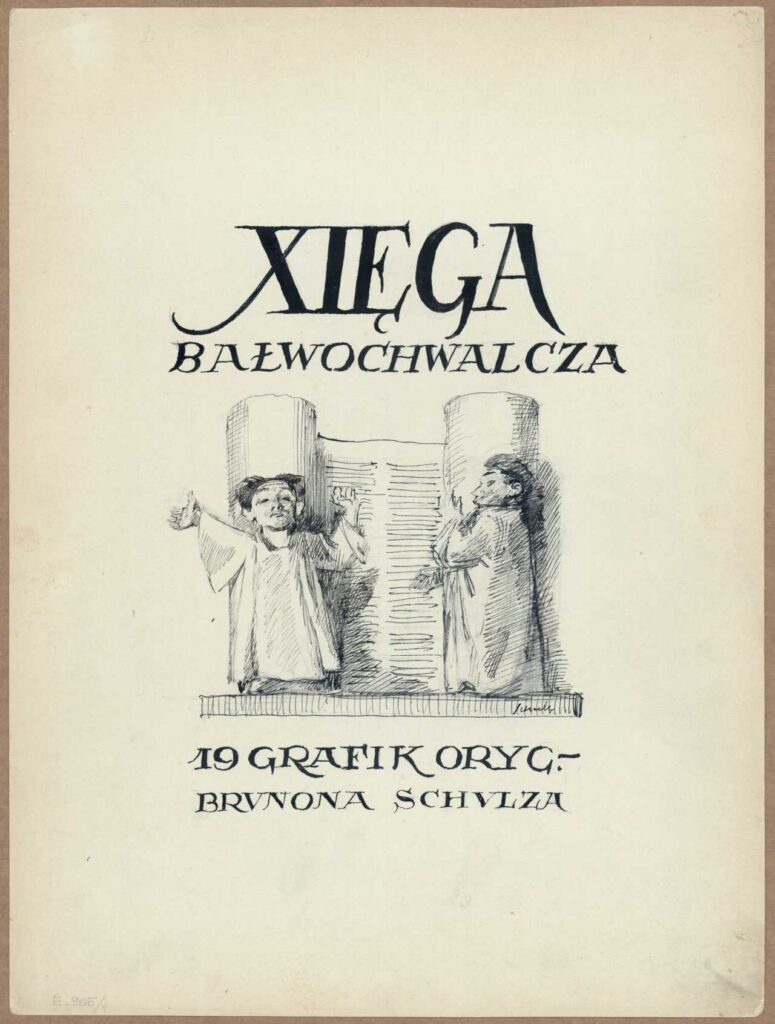

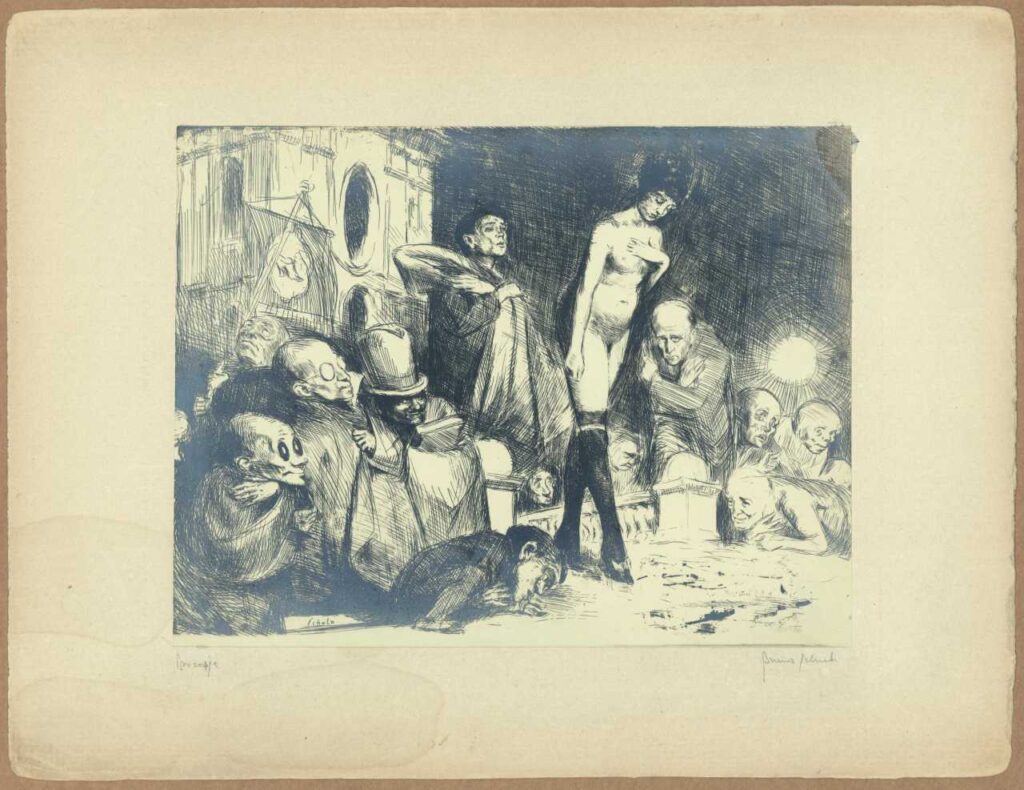

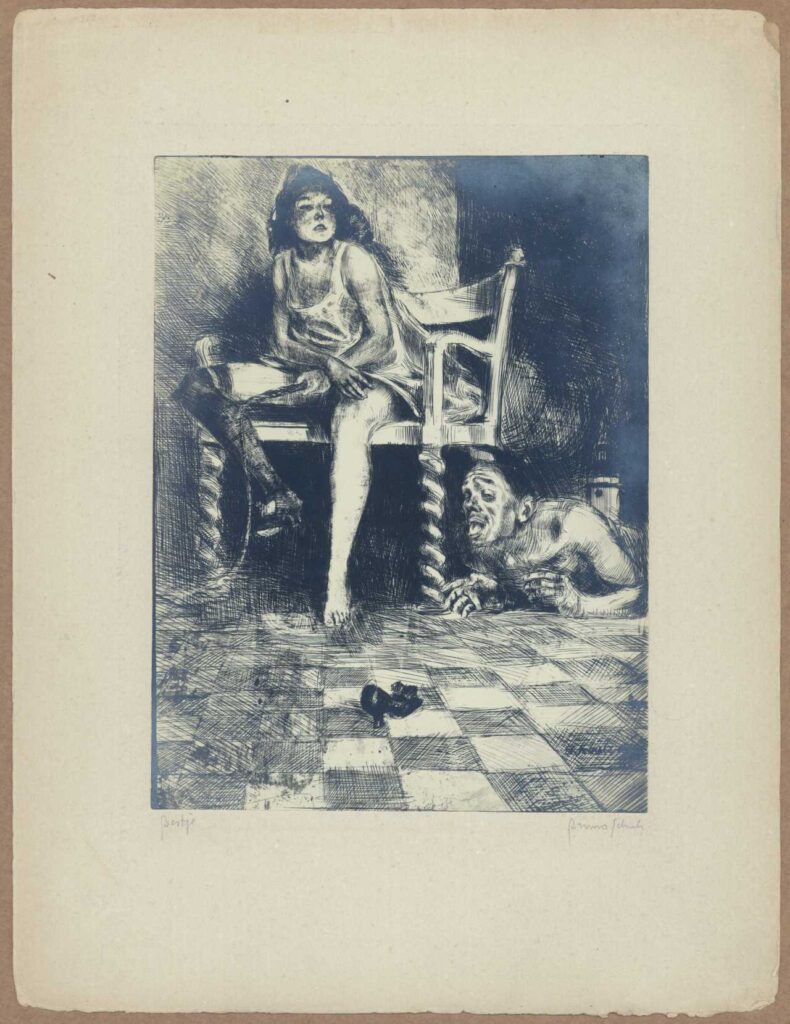

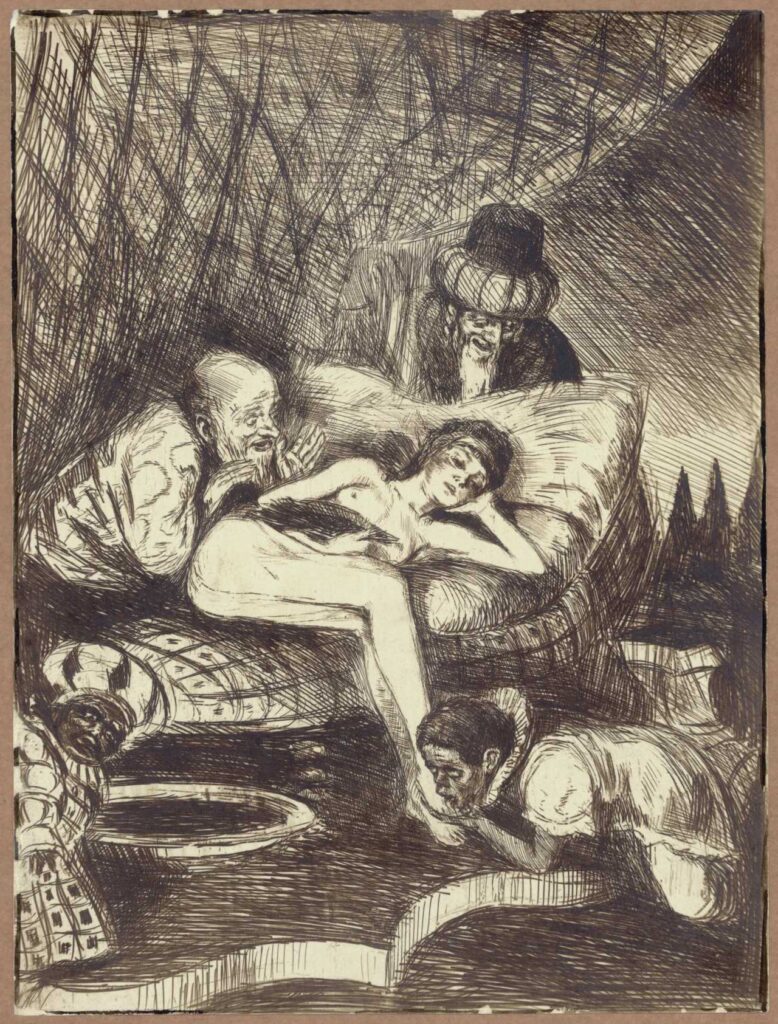

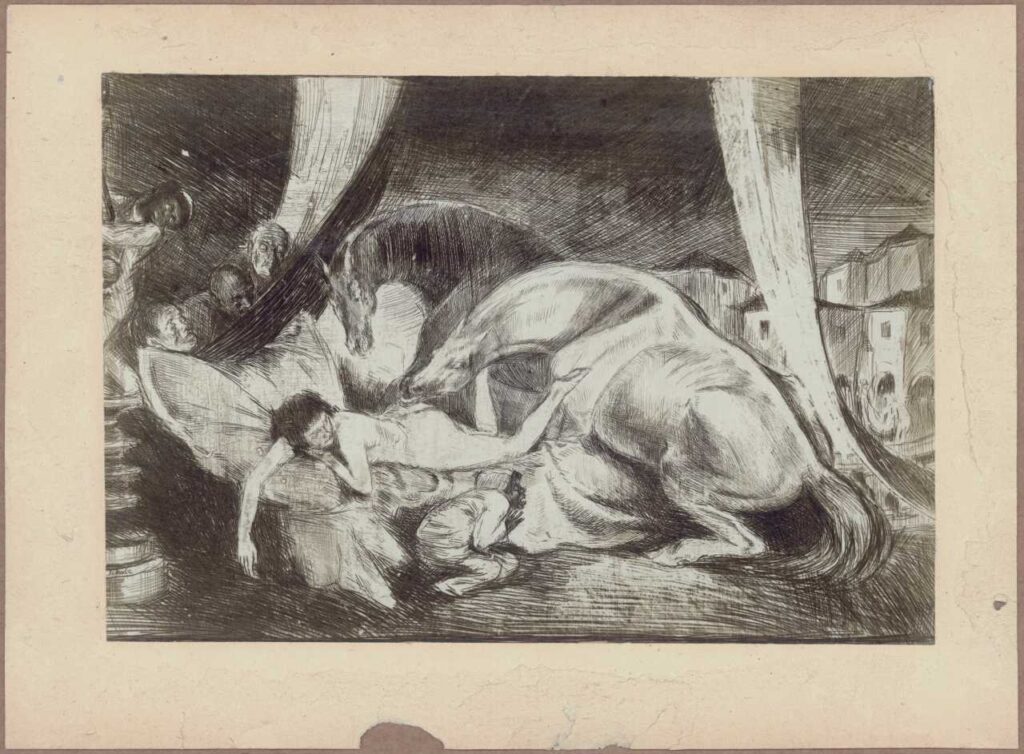

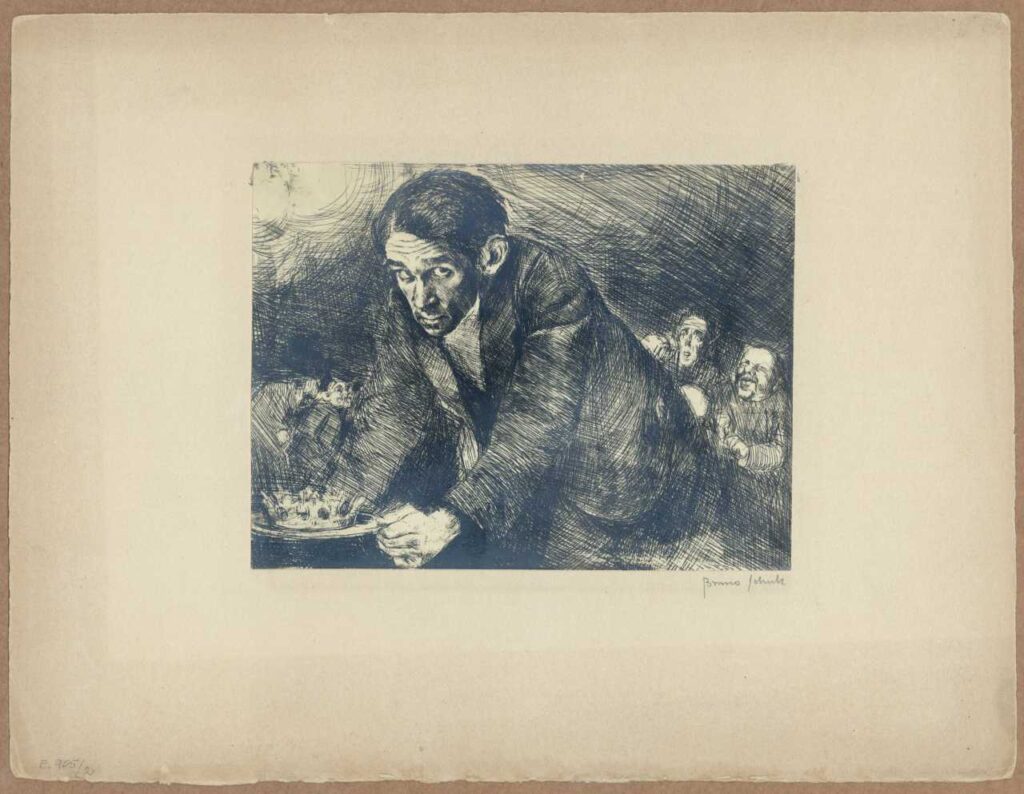

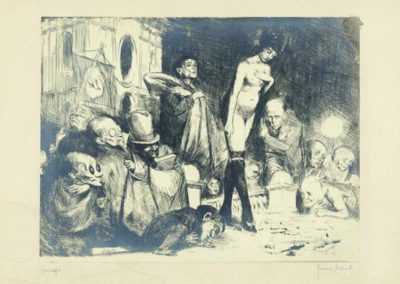

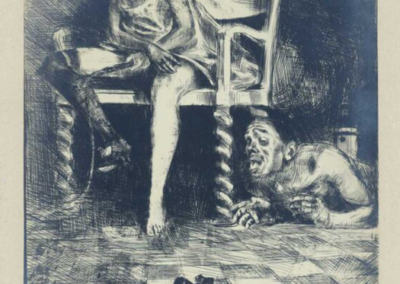

Spisovatel, grafik, malíř a kreslíř pocházející z Drohobyče. Autor povídkových sbírek Skořicové krámy a Sanatorium na věčnosti – próz hojně čtených a analyzovaných na celém světě. Někteří jeho následovníci jej nazývají tvůrčím géniem a mýtickou postavou, jež dodnes přináší inspiraci řadě dalších umělců.

Narodil se 12. července 1892 v městečku Drohobyč (dnešní Ukrajina), v rodině kupce s textiliemi. Jeho rodina sice byla součástí místní židovské náboženské obce, nicméně nikdo z nich nebyl praktikující a doma se mluvilo jen polsky. Schulzův rodný dům autor dopodrobna popsal v povídkové sbírce Skořicové krámy. Po maturitě studoval architekturu na VUT v nedalekém Lvově. Během první světové války rodina strávila několik měsíců ve Vídni. Po smrti otce v roce 1915 za něj Bruno převzal odpovědnost živitele rodiny. V roce 1924 získal první stálé zaměstnání jako učitel kreslení (a později i ručních prací) na gymnáziu v Drohobyči.

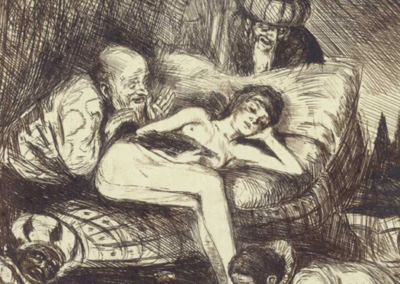

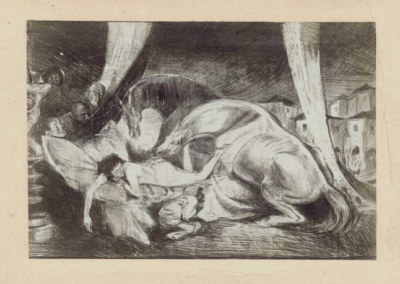

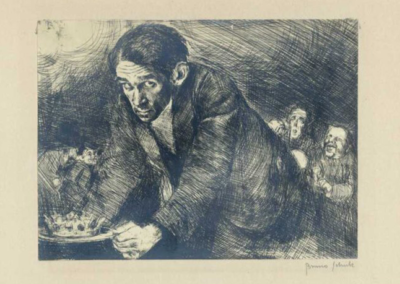

Jako spisovatel debutoval až v roce 1933, kdy byla v literárním časopise „Wiadomości Literackie” zveřejněna jeho povídka Ptáci. Ve stejném roce, díky podpoře spisovatelky Zofie Nałkowské, vyšla jeho sbírka povídek Skořicové krámy. Skromný kantor z malého městečka tak rychle získal slávu a stal se významnou osobností varšavského literárního prostředí. V roce 1937 následovalo vydání povídkové sbírky Sanatorium na věčnosti. Schulz udržoval čilý styk s řadou dalších umělců a spisovatelů, mj. s Witoldem Gombrowiczem, Arturem Sandauerem, S. I. Witkiewiczem alias Witkacym a Deborou Vogel. Jeho prozaické, stejně jako výtvarné dílo vypovídají o temných zákoutích a komplexní podobě autorova vnitřního života. Dodnes se pátrá po nevydaném rukopise Schulzova mysteriózního románu Mesiáš, který se měl zachovat v jediném exempláři.

Nacisté okupovali Drohobyč v roce 1941. Bruno Schulz byl poté delegován „pod patronát“ nechvalně známého velitele Gestapa Felixe Landaua, pro nějž na zakázku tvořil nejrůznější obrazy. Nakonec byl 19. listopadu 1942 na ulici svého rodného města zastřelen jiným členem Gestapa. Schulzova tvorba se dodnes těší obrovskému zájmu badatelů a čtenářů na celém světě.

kreativita

kreativita

Spring, XIV

Translated into English by Celina Wieniewska

A band is now playing every evening in the city park, and people on their spring outings fill the avenues. They walk up and down, pass one another, and meet again in symmetrical, continuously repeated patterns. The young men are wearing new spring hats and nonchalantly carrying gloves in their hands. Through the hedges and between the tree trunks the dresses of girls walking in parallel avenues glow. The girls walk in pairs, swinging their hips, strutting like swans under the foam of their ribbons and flounces; sometimes they land on garden seats as if tired by the idle parade, and the bells of their flowered muslin skirts expand on the seats, like roses beginning to shed their petals. And then they disclose their crossed legs – white irresistibly expressive shapes – and the young men, passing them, grow speechless and pale, hit by the accuracy of the argument, completely convinced and conquered.

At a particular moment before dusk all the colors of the world become more beautiful than ever, festive, ardent yet sad. The park quickly fills with pink varnish, with shining lacquer that makes every other color glow deeper; and at the same time the beauty of the colors becomes too glaring and somewhat suspect. In another instant the thickets of the park strewn with young greenery, still naked and twiggy, fill with the pinkness of dusk, shot with coolness, spilling the indescribable sadness of things supremely beautiful but mortal.

Then the whole park becomes an enormous, silent orchestra, solemn and composed, waiting under the raised baton of the conductor for its music to ripen and rise; and over that potential, earnest symphony a quick theatrical dusk spreads suddenly as if brought down by the sounds swelling in the instruments. Above, the young greenness of the leaves is pierced by the tones of an invisible oriole, and once everything turns somber, lonely, and late, like an evening forest.

A hardly perceptible breeze sails through the treetops, from which dry petals of cherry blossom fall in a shower. A tart scent drifts high under the dusky sky and floats like a premonition of death, and the first stars shed their tears like lilac blooms picked from pale, purple bushes.

It is then that a strange desperation grips the youths and young girls walking up and down and meeting at regular intervals. Each man transcends himself, becomes handsome and irresistible like a Don Juan, and his eyes express a murderous strength that chills a woman’s heart. The girls’ eyes sink deeper and reveal dark labyrinthine pools. Their pupils distend, open without resistance, and admit those conquerors who stare into their opaque darkness. Hidden paths of the park reveal themselves and lead to thickets, ever deeper and more rustling, in which they lose themselves, as in a backstage tangle of velvet curtains and secluded corners. And no one knows how they reach, through the coolness of these completely forgotten darkened gardens, the strange spots where darkness ferments and degenerates, and vegetation emits a smell like the sediment in long-forgotten wine barrels.

Wandering blindly in the dark plush of the gardens, the young people meet at last in an empty clearing, under the last purple glow of the setting sun, over a pond that has been growing muddy for years; on a rotting balustrade, somewhere at the back gate of the world, they find themselves again in pre-existence, a life long past, in attitudes of a distant age; they sob and plead, rise to promises never to be fulfilled, and, climbing up the steps of exaltation, reach summits and climaxes beyond which there is only death and numbness of nameless delight.