Main Page > Literature > Bruno Shulz

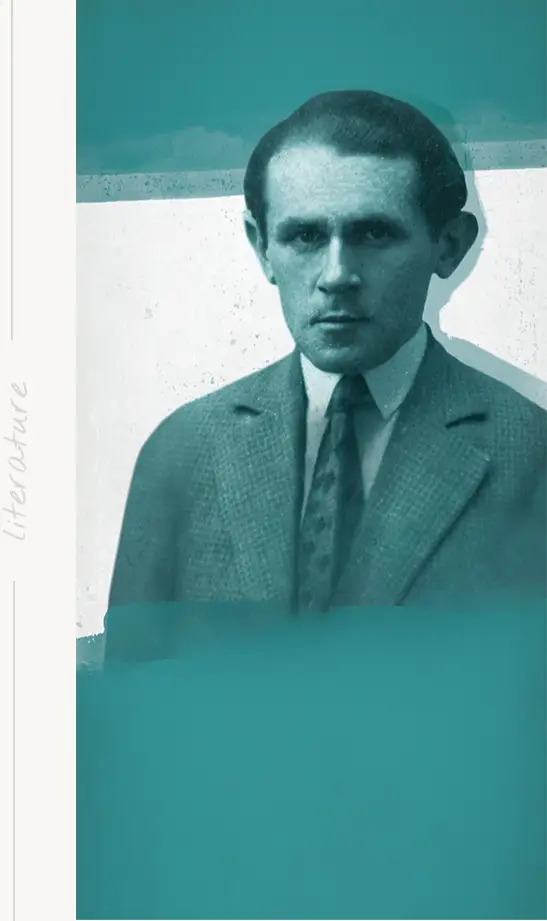

Bruno Shulz

12 VII 1892, Drohobytsch — 19 XI 1942, Drohobytsch (today‘s Ukraine)

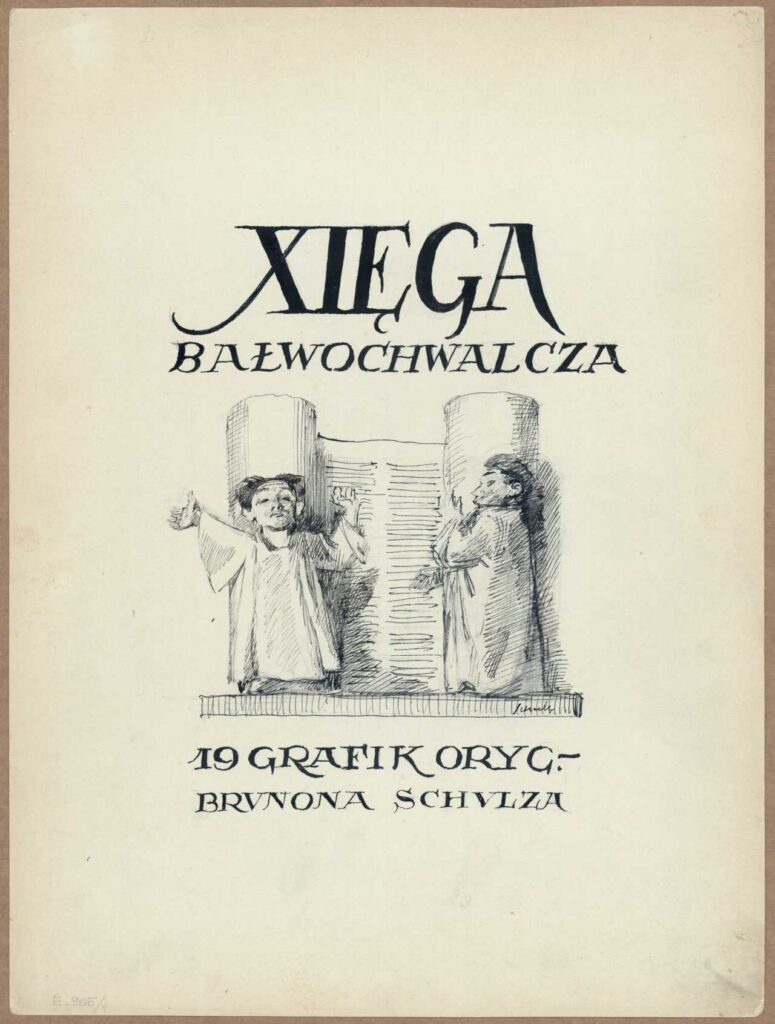

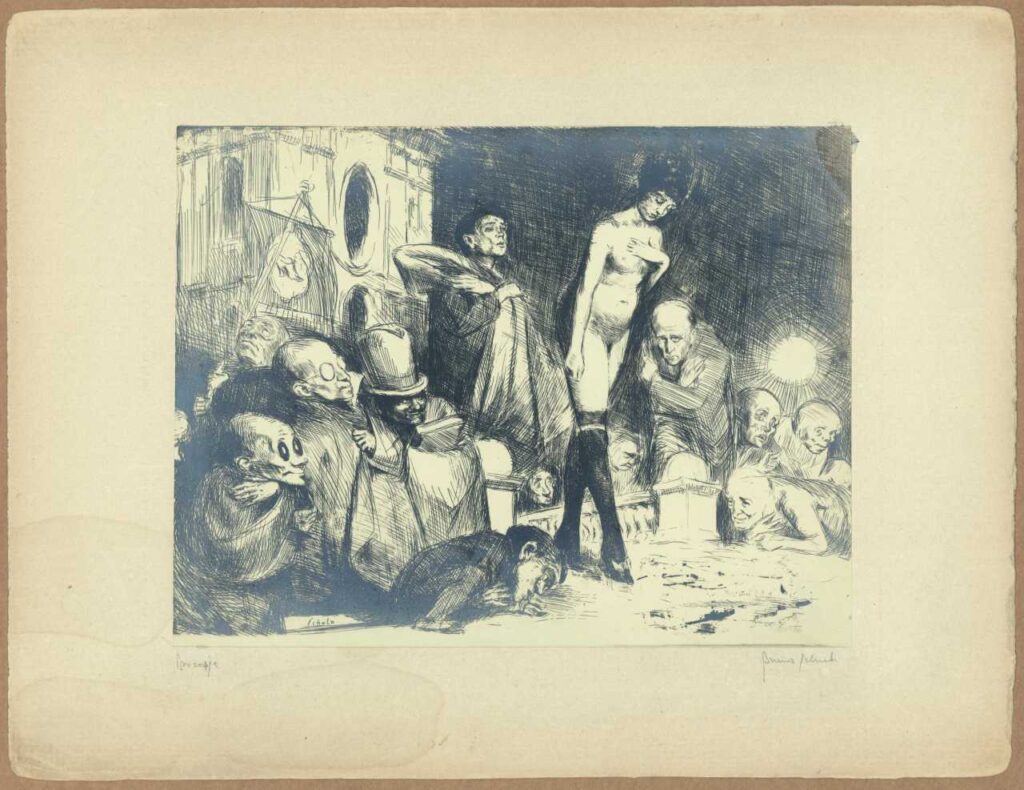

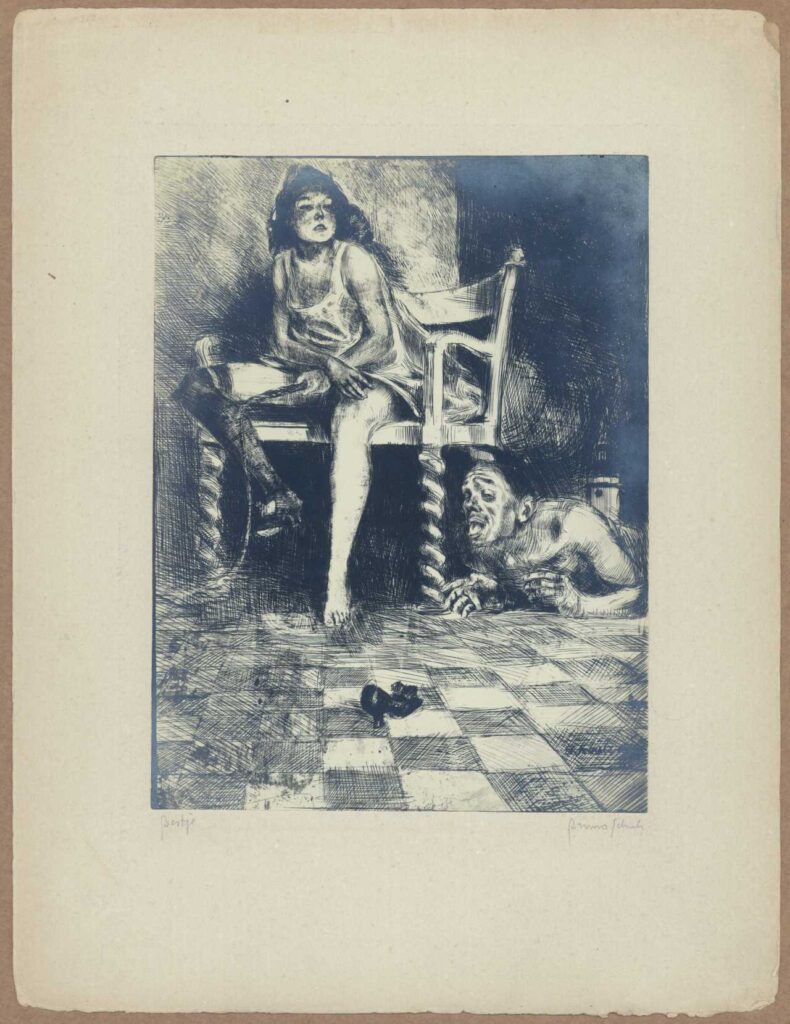

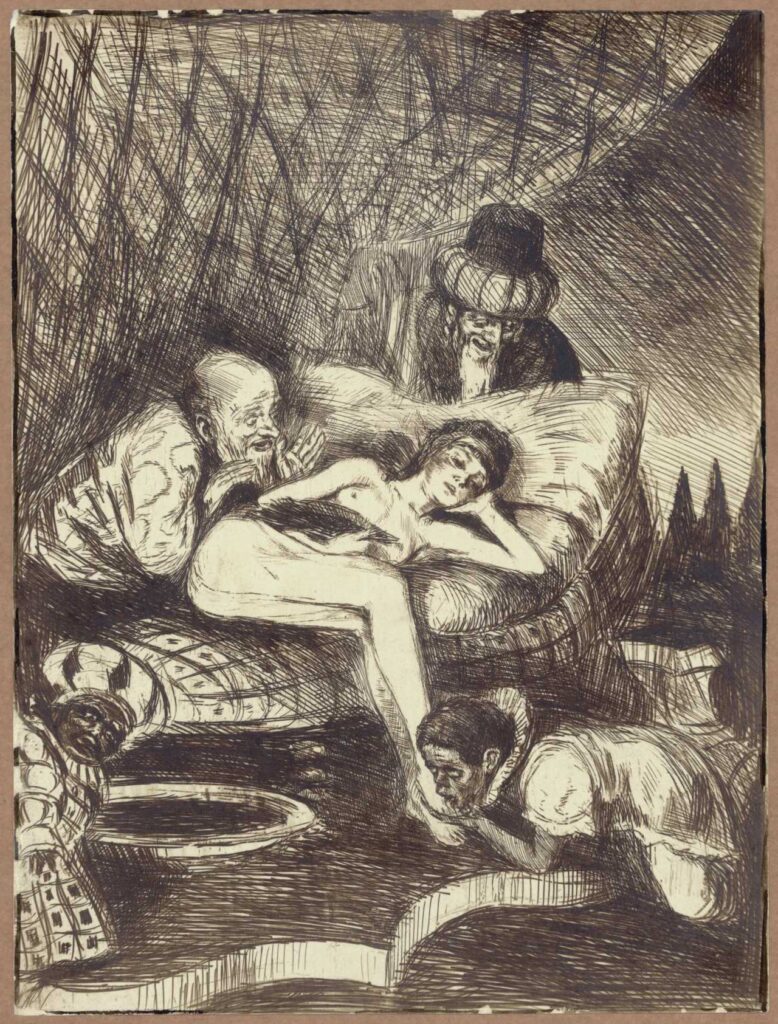

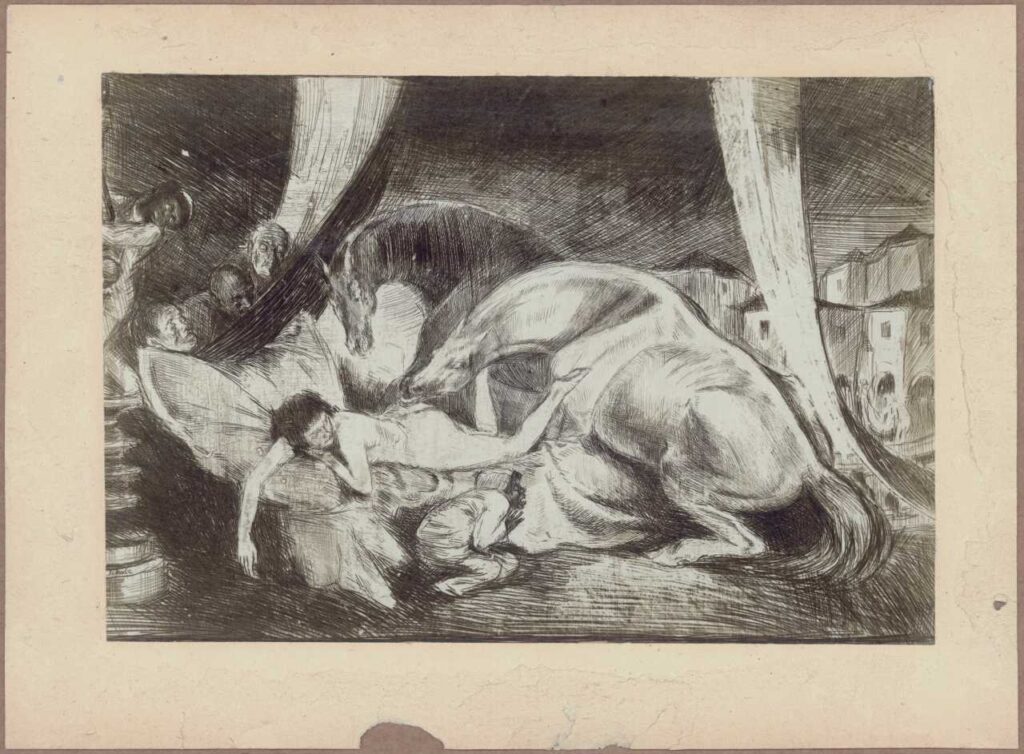

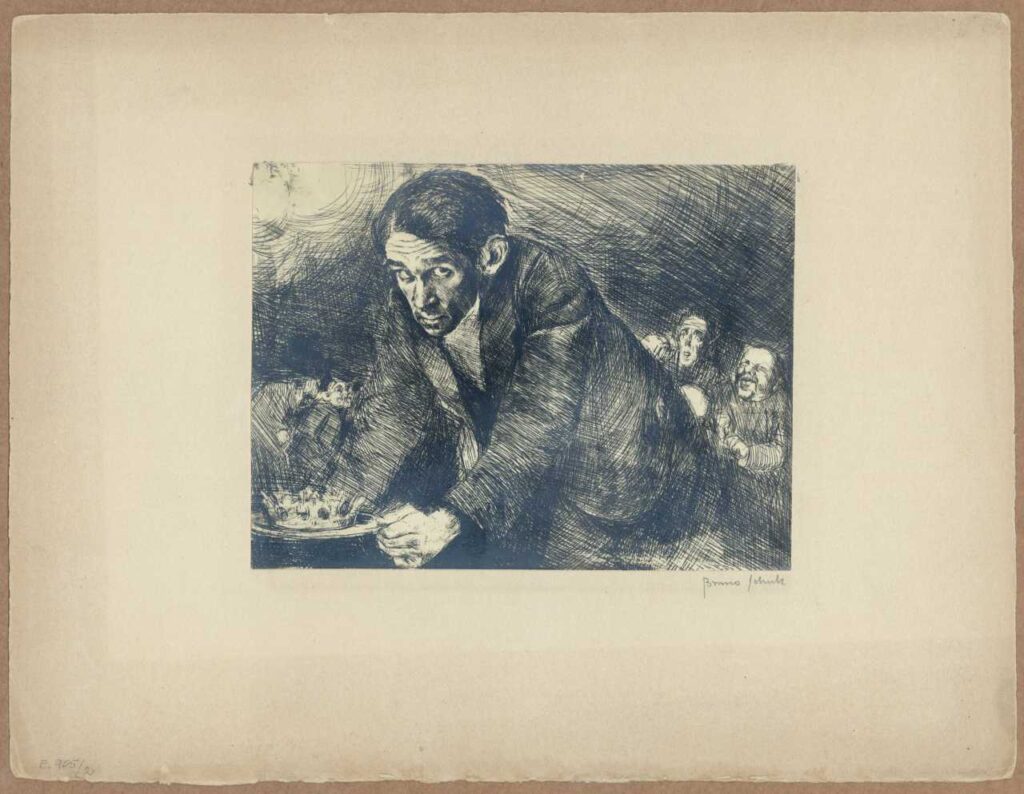

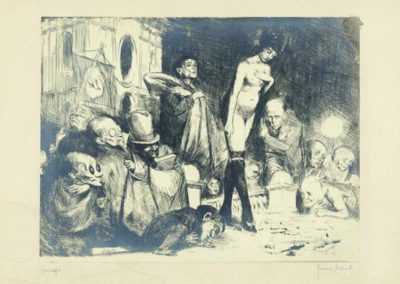

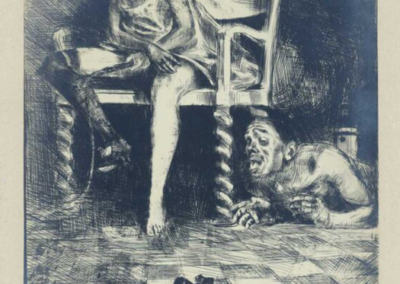

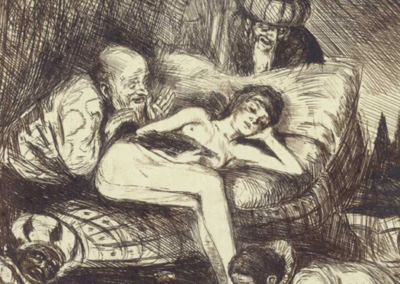

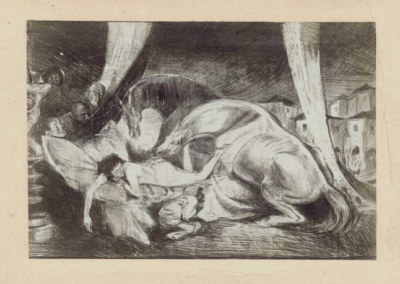

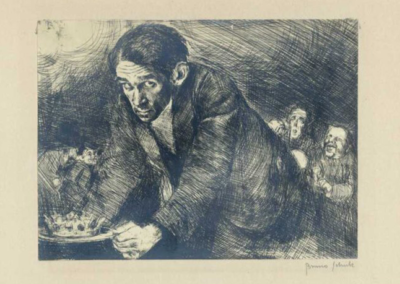

Bruno Schulz was a writer, graphic artist, painter, and draughtsman. His two collections of short stories, The Street of Crocodiles and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass, are still widely read and analyzed worldwide. Regarded by many as a creative genius and mythical figure, he continues to be an inspiration for other artists to this day.

Bruno Schulz was born on 12 July,1892 to a cloth merchant’s family living in Drohobycz (today’s Ukraine). His family was part of the Jewish community, however, they did not live according to Jewish customs and chose Polish, instead of Yiddish, as their language. In his writings he immortalized the tenant building in which he lived, describing it in a series of short stories which were published under the title Cinnamon Shops (in English known as The Street of Crocodiles). Upon graduating from upper secondary school, he studied architecture at Lviv Polytechnic. During World War I, Schulz’s family spent several months in Vienna. When his father died, he assumed responsibility for supporting the family. In 1924, Bruno Schulz took up a position in a middle school in Drohobycz, first as an art teacher, and later also as a handicraft teacher.

His literary début came in 1933 with the publication of the short story Birds in the literary magazine Wiadomości Literackie (‘Literary News’); in fact, The Street of Crocodiles was published in the same year thanks to the support of another Polish writer, Zofia Nałkowska. Despite remaining a modest teacher from a small town, Bruno Schultz quickly became a famous and significant figure in the Warsaw literary scene. In 1937, he published a second collection of short stories, Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass. He kept in touch with many artists and writers of the era, including Witold Gombrowicz, Artur Sandauer, Witkacy (Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz), and Debora Vogel. Both his art and writings reflect foremostly the intricacies and complexities of his internal life. His enigmatic unpublished novel, The Messiah is believed to have survived the war, and the search for the missing manuscript continues to this day.

In 1941, when the Germans entered Drohobycz, Felix Landau, a Gestapo officer renowned for his cruelty, extended his “protection” to Bruno Schulz, ordering him to produce various works of art in return. Ultimately, Schulz died at the hands of another Gestapo officer who shot him in the street of his hometown on 19 November, 1942. His work, however, lives on, continuing to attract the interest of researchers and readers worldwide.

Spring, XIV

Translated into English by Celina Wieniewska

A band is now playing every evening in the city park, and people on their spring outings fill the avenues. They walk up and down, pass one another, and meet again in symmetrical, continuously repeated patterns. The young men are wearing new spring hats and nonchalantly carrying gloves in their hands. Through the hedges and between the tree trunks the dresses of girls walking in parallel avenues glow. The girls walk in pairs, swinging their hips, strutting like swans under the foam of their ribbons and flounces; sometimes they land on garden seats as if tired by the idle parade, and the bells of their flowered muslin skirts expand on the seats, like roses beginning to shed their petals. And then they disclose their crossed legs – white irresistibly expressive shapes – and the young men, passing them, grow speechless and pale, hit by the accuracy of the argument, completely convinced and conquered.

At a particular moment before dusk all the colors of the world become more beautiful than ever, festive, ardent yet sad. The park quickly fills with pink varnish, with shining lacquer that makes every other color glow deeper; and at the same time the beauty of the colors becomes too glaring and somewhat suspect. In another instant the thickets of the park strewn with young greenery, still naked and twiggy, fill with the pinkness of dusk, shot with coolness, spilling the indescribable sadness of things supremely beautiful but mortal.

Then the whole park becomes an enormous, silent orchestra, solemn and composed, waiting under the raised baton of the conductor for its music to ripen and rise; and over that potential, earnest symphony a quick theatrical dusk spreads suddenly as if brought down by the sounds swelling in the instruments. Above, the young greenness of the leaves is pierced by the tones of an invisible oriole, and once everything turns somber, lonely, and late, like an evening forest.

A hardly perceptible breeze sails through the treetops, from which dry petals of cherry blossom fall in a shower. A tart scent drifts high under the dusky sky and floats like a premonition of death, and the first stars shed their tears like lilac blooms picked from pale, purple bushes.

It is then that a strange desperation grips the youths and young girls walking up and down and meeting at regular intervals. Each man transcends himself, becomes handsome and irresistible like a Don Juan, and his eyes express a murderous strength that chills a woman’s heart. The girls’ eyes sink deeper and reveal dark labyrinthine pools. Their pupils distend, open without resistance, and admit those conquerors who stare into their opaque darkness. Hidden paths of the park reveal themselves and lead to thickets, ever deeper and more rustling, in which they lose themselves, as in a backstage tangle of velvet curtains and secluded corners. And no one knows how they reach, through the coolness of these completely forgotten darkened gardens, the strange spots where darkness ferments and degenerates, and vegetation emits a smell like the sediment in long-forgotten wine barrels.

Wandering blindly in the dark plush of the gardens, the young people meet at last in an empty clearing, under the last purple glow of the setting sun, over a pond that has been growing muddy for years; on a rotting balustrade, somewhere at the back gate of the world, they find themselves again in pre-existence, a life long past, in attitudes of a distant age; they sob and plead, rise to promises never to be fulfilled, and, climbing up the steps of exaltation, reach summits and climaxes beyond which there is only death and numbness of nameless delight.