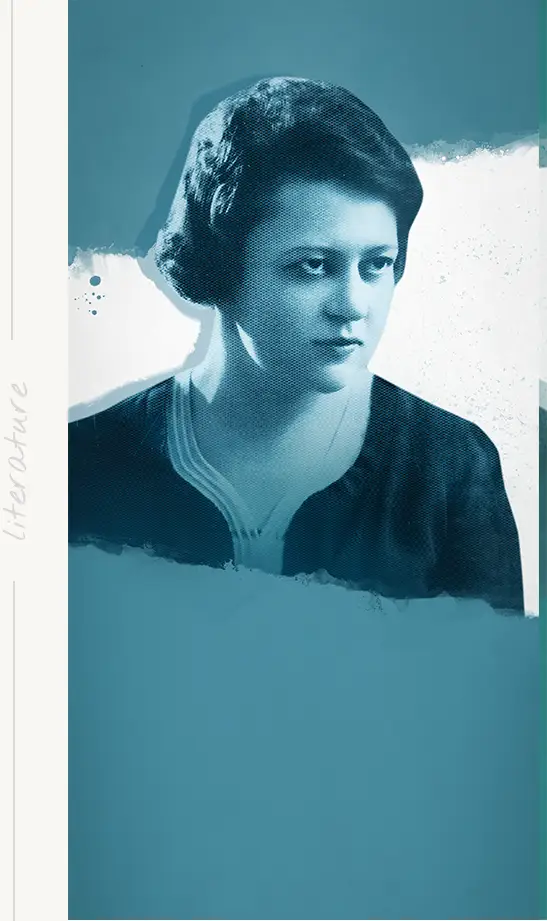

Debora Vogel

4 I 1900, Burshtyn (today’s Ukraine) — VIII 1942, Lviv Ghetto

Debora Vogel was a poet as well as a literary and art critic writing mainly in Polish and Yiddish. Her experimental works combined poetry and visual arts.

She was born in 1900, in the small town of Burshtyn in Galicia (today’s Ukraine). During World War I, her family fled first to Vienna and later to Lviv where Debora Vogel spent most of her life.German was her language of choice when she began writing, but her first published work was written in Polish. Rachel Auerbach, a writer and advocate of modern Yiddish culture, encouraged her to try her hand at writing in Yiddish, even though it was not spoken at her home. Ultimately, she decided to write in Polish, Hebrew, and Yiddish. She was active in Yiddish literary circles and wrote for Polish-language newspapers. Debora Vogel published essays on poetry, as well as art reviews and poems. She was a friend of the writer and artist Bruno Schulz.

Experimentation was the driving force behind Debora Vogel’s poetry. Written mainly in the 1930s, her poems incorporated both radicalism and minimalism which became the characteristic features of her work. Her poetic experiments combined poetry and visual arts, using a method she referred to as the “white words” technique. She published two volumes of poems Tog-figurn (‘Figures of the Day’, 1930) and Manekinen (‘Mannequins’, 1934), as well as a collection of montages titled “Acacias Bloom” which appeared in two linguistic versions: in Yiddish in 1935, titled Akacjes blien, and, in Polish in 1936, as Akacje kwitną.

In 1932, Debora married Szulim Barenblüth, a Lviv architect and engineer. Their only son, Anshel, was born four years later. When the city was taken over by the Nazis, the family ended up in the Lviv Ghetto, where they were murdered during its liquidation in 1942.

creativity

creativity

Poem on waiting (2)

translated into English by Anastasiya Lyubas

I have worn out

all my dresses

waiting for you.

I put them on the first time

took them off the last time

in a month of sticky sun, in a month of tired leaves

in the evening garden

a chestnut red dress,

ready to wrap me

soft as velvet.

The rust-gold dress

for the month of tired leaves

and bleak flowers’ second blossoms.

And a coral-colored dress,

in which I look like a cold coral

in the glass sea of afternoon streets

with a smell of the seaweed of bodies.

Never again

will I worry what dress to wear for you.

In: Blooming Spaces: The Collected Poetry, Prose, Critical Writing, and Letters of Debora Vogel,

translated, edited, and with an introduction by Anastasiya Lyubas, Boston 2020.

A poem of colors

translated into English by Anastasiya Lyubas

The white is flat:

a usual house seen from up front,

a boring house where nothing happens,

a flat paper rectangle, which wants nothing.

The gray is long and round.

You have nowhere to go, so similar are the houses.

And you go. Go impatiently along streets

until the street grayness gives out

and closes round the dwelling where you live.

The yellow elastic heat tin,

the tin yellow is deep.

Like the distance of things that do not return.

In: Blooming Spaces: The Collected Poetry, Prose, Critical Writing, and Letters of Debora Vogel,

translated, edited, and with an introduction by Anastasiya Lyubas, Boston 2020.

Ze zbiorów Muzeum Literatury im. Adama Mickiewicza w Warszawie

Dolls

translated into English by Anastasiya Lyubas

She stood for a long time

like a half act of porcelain

behind a milky windowpane

BARBER’S SHOP—BROAD STREET—15.

She was kneaded

from red porcelain dough

of women’s bodies by Rubens

and seduces with two pink breast-apples

as if with round shiny eyes.

With half-open eyes

the porcelain smiled

smooth and watery, as if enchanted

by everything which happens in the world

on the second, the other side of the window.

And on the other side of shop window

elastic dolls stroll

with sweet long almonds of eyes

and agile hands and feet.

Dolls with a movable heart

carry glassy pupils of eyes under eyelashes with mascara

and a carmine smile of Chameleon brand

and faces of smiling porcelain.

At the same time

pink dolls at fifteen Broad Street

show their lively breasts like round apples

and sadness like squandered happiness.

In: Blooming Spaces: The Collected Poetry, Prose, Critical Writing, and Letters of Debora Vogel,

translated, edited, and with an introduction by Anastasiya Lyubas, Boston 2020.