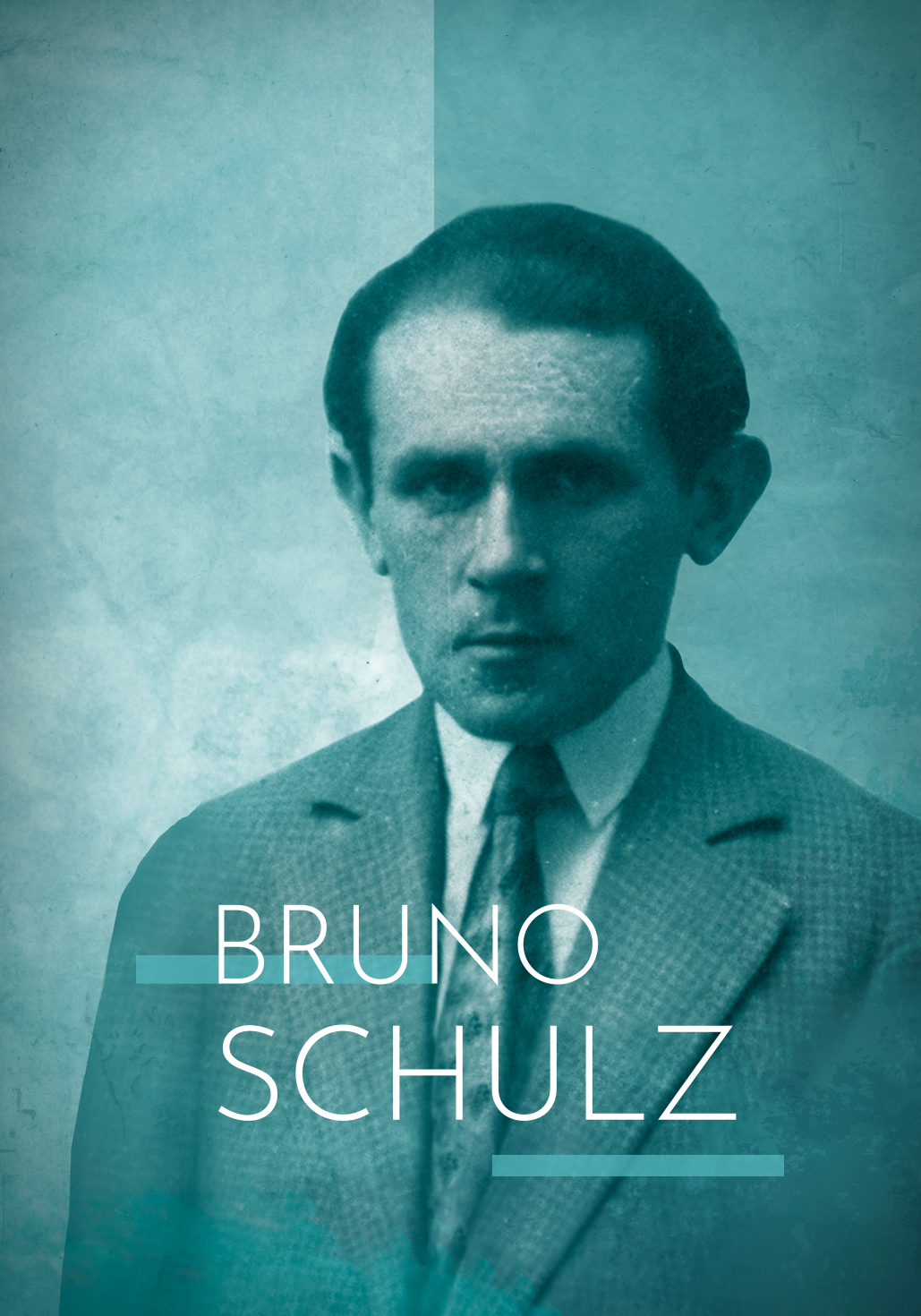

12 VII 1892, Drohobytsch – 19 XI 1942, Drohobytsch (i dag Ukraina)

Biografi

Bruno Schulz var forfatter, grafiker, maler og tegner. Han ble født i Drohobycz, i det som etter hvert ble en del av Polen, og som i dag er en del av Ukraina. De to novellesamlingene hans, Kanelbutikkene og Sanatorium under timeglassets tegn blir fortsatt lest over hele verden. Bruno Schulz har fått status som ikon og geni, og han og inspirerer fremdeles forfattere.

Bruno ble født 12. juli 1892. Familien drev en klesbutikk i Drohobycz. De var en del av det jødiske miljøet, men fulgte ikke alle de jødiske tradisjonene. Området han vokste opp i, var et møtested for mange ulike kulturer og språk, men Schulz-familien snakket polsk hjemme. Hjembyen hans er blitt udødeliggjort i Kanelbutikkene. Han begynte å studere arkitektur ved den polytekniske høyskolen i Lviv, men da første verdenskrig brøt ut, måtte familien tilbringe flere måneder i Wien. Da faren døde, ble det opp til Bruno å forsørge familien, og i 1924 fikk han jobb som lærer på en ungdomsskole i Drohobycz, først som kunstlærer, og senere også som håndverkslærer.

Bruno Schulz debuterte i 1933 med novellen «Fuglene» i det litterære magasinet Wiadomości Literackie. Mye takket være den polske forfatteren Zofia Nałkowska (1884–1954) ble novellesamlingen Kanelbutikkene publisert samme år. Schulz ble raskt en viktig skikkelse i det litterære miljøet i Warszawa. Både Witold Gombrowicz, Artur Sandauer, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (oftest kjent som Witkacy) og Debora Vogel var en del av omgangskretsen hans. I 1937 ga han ut novellesamlingen Sanatorium under timeglassets tegn. Litteraturen hans springer ut av et sammensatt og komplekst indre liv og framstår som svært fargerik. Bruno Schulz har vært sammenlignet med Kafka. Den upubliserte romanen hans Messias er myteomspunnet. Manuskriptet kom bort etter at han døde, men man antar at det overlevde krigen.

Da tyskerne kom til Drohobycz i 1941, kom Schulz under Gestapo-offiseren Felix Landaus «beskyttelse». Til gjengjeld måtte Schulz produsere ulike kunstverk. Schulz ble likevel skutt av en Gestapo-offiser i hjembyen sin den 19. november 1942. Kunsten hans lever imidlertid videre og fortsetter å tiltrekke seg interesse fra forskere og lesere over hele verden.

Bruno Schulz var forfatter, grafiker, maler og tegner. Han ble født i Drohobycz, i det som etter hvert ble en del av Polen, og som i dag er en del av Ukraina. De to novellesamlingene hans, Kanelbutikkene og Sanatorium under timeglassets tegn blir fortsatt lest over hele verden. Bruno Schulz har fått status som ikon og geni, og han og inspirerer fremdeles forfattere.

Bruno ble født 12. juli 1892. Familien drev en klesbutikk i Drohobycz. De var en del av det jødiske miljøet, men fulgte ikke alle de jødiske tradisjonene. Området han vokste opp i, var et møtested for mange ulike kulturer og språk, men Schulz-familien snakket polsk hjemme. Hjembyen hans er blitt udødeliggjort i Kanelbutikkene. Han begynte å studere arkitektur ved den polytekniske høyskolen i Lviv, men da første verdenskrig brøt ut, måtte familien tilbringe flere måneder i Wien. Da faren døde, ble det opp til Bruno å forsørge familien, og i 1924 fikk han jobb som lærer på en ungdomsskole i Drohobycz, først som kunstlærer, og senere også som håndverkslærer.

Bruno Schulz debuterte i 1933 med novellen «Fuglene» i det litterære magasinet Wiadomości Literackie. Mye takket være den polske forfatteren Zofia Nałkowska (1884–1954) ble novellesamlingen Kanelbutikkene publisert samme år. Schulz ble raskt en viktig skikkelse i det litterære miljøet i Warszawa. Både Witold Gombrowicz, Artur Sandauer, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (oftest kjent som Witkacy) og Debora Vogel var en del av omgangskretsen hans. I 1937 ga han ut novellesamlingen Sanatorium under timeglassets tegn. Litteraturen hans springer ut av et sammensatt og komplekst indre liv og framstår som svært fargerik. Bruno Schulz har vært sammenlignet med Kafka. Den upubliserte romanen hans Messias er myteomspunnet. Manuskriptet kom bort etter at han døde, men man antar at det overlevde krigen.

Da tyskerne kom til Drohobycz i 1941, kom Schulz under Gestapo-offiseren Felix Landaus «beskyttelse». Til gjengjeld måtte Schulz produsere ulike kunstverk. Schulz ble likevel skutt av en Gestapo-offiser i hjembyen sin den 19. november 1942. Kunsten hans lever imidlertid videre og fortsetter å tiltrekke seg interesse fra forskere og lesere over hele verden.

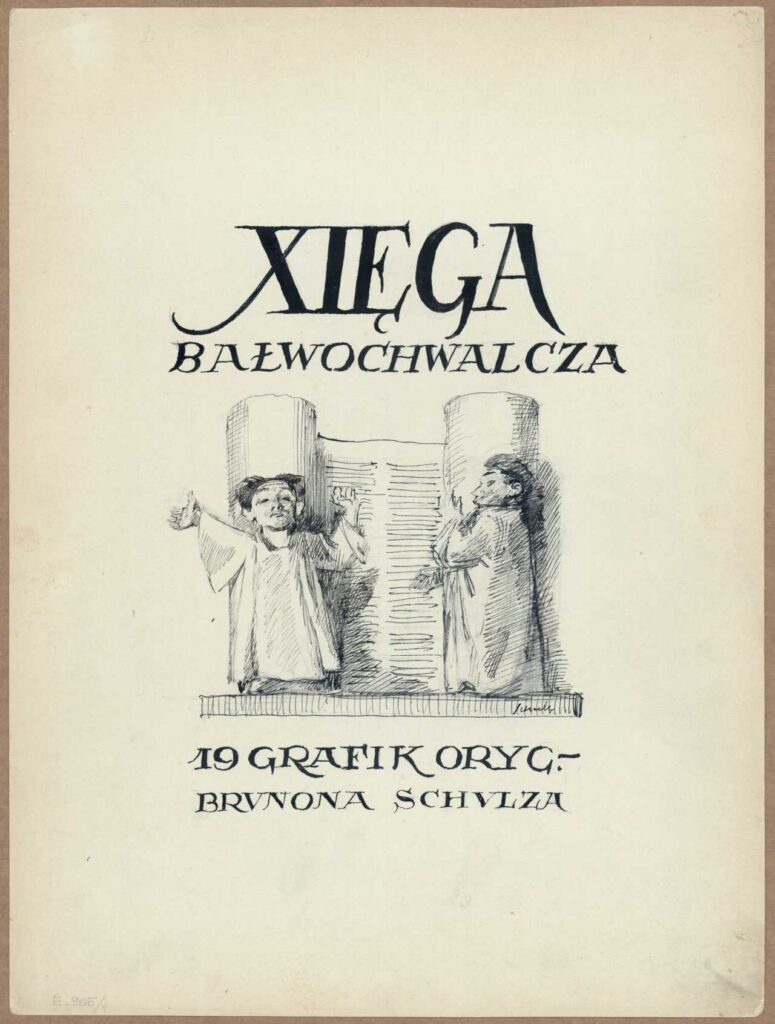

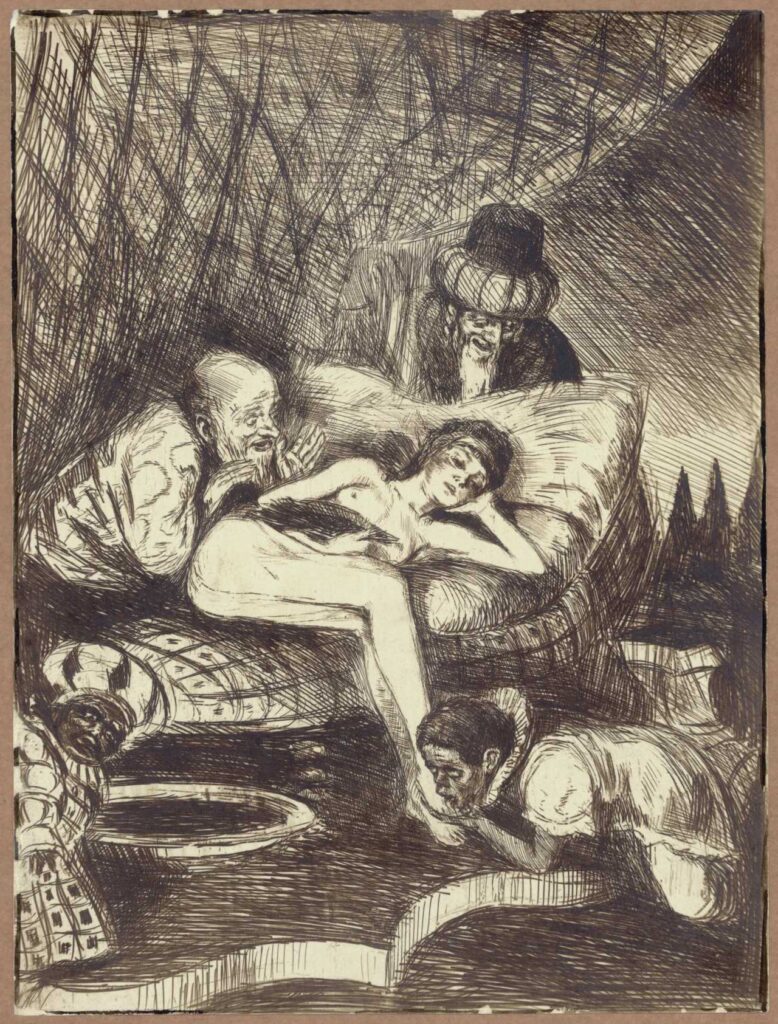

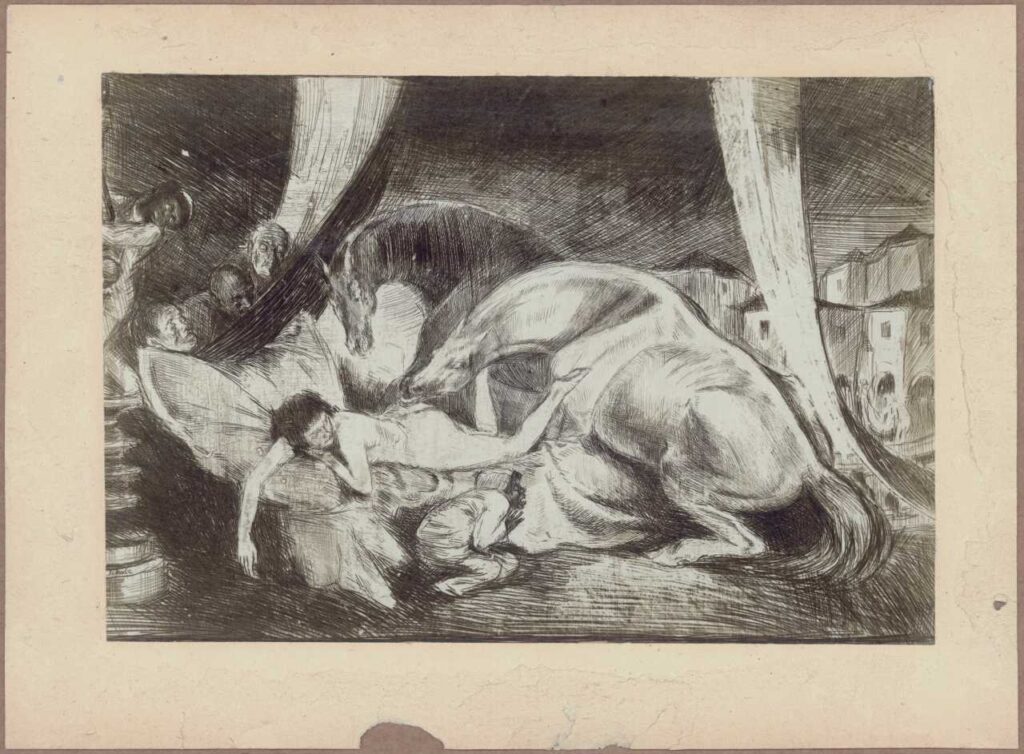

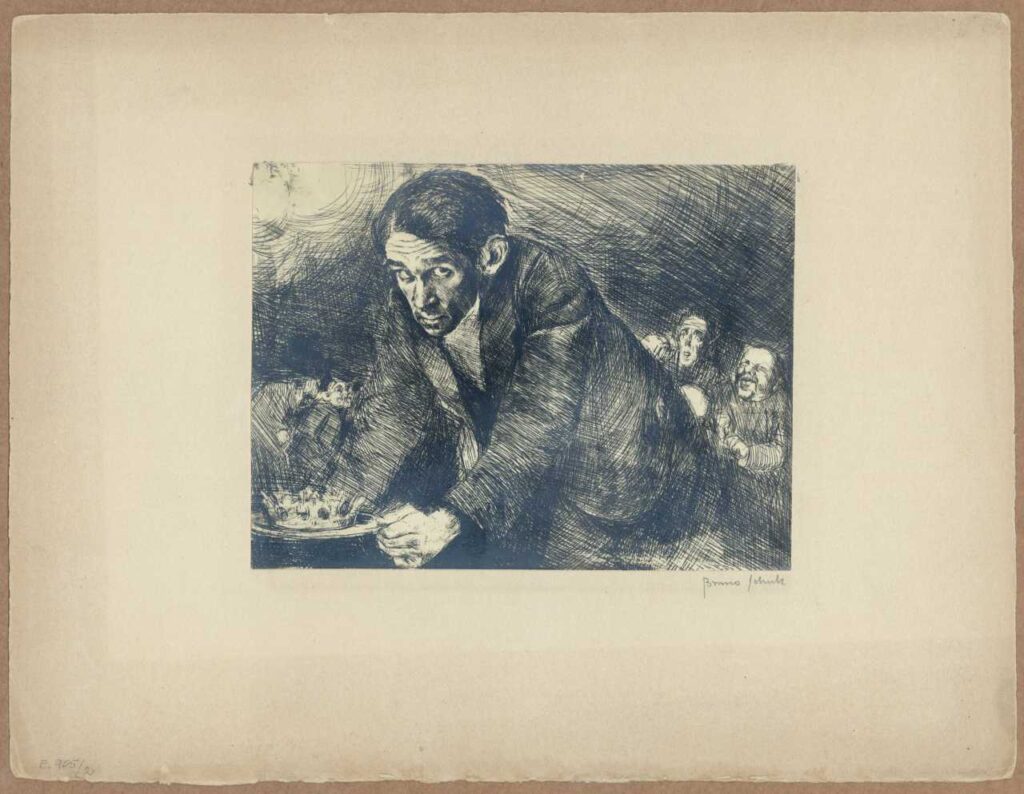

From the collection of The Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature in Warsaw

From the collection of The Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature in Warsaw

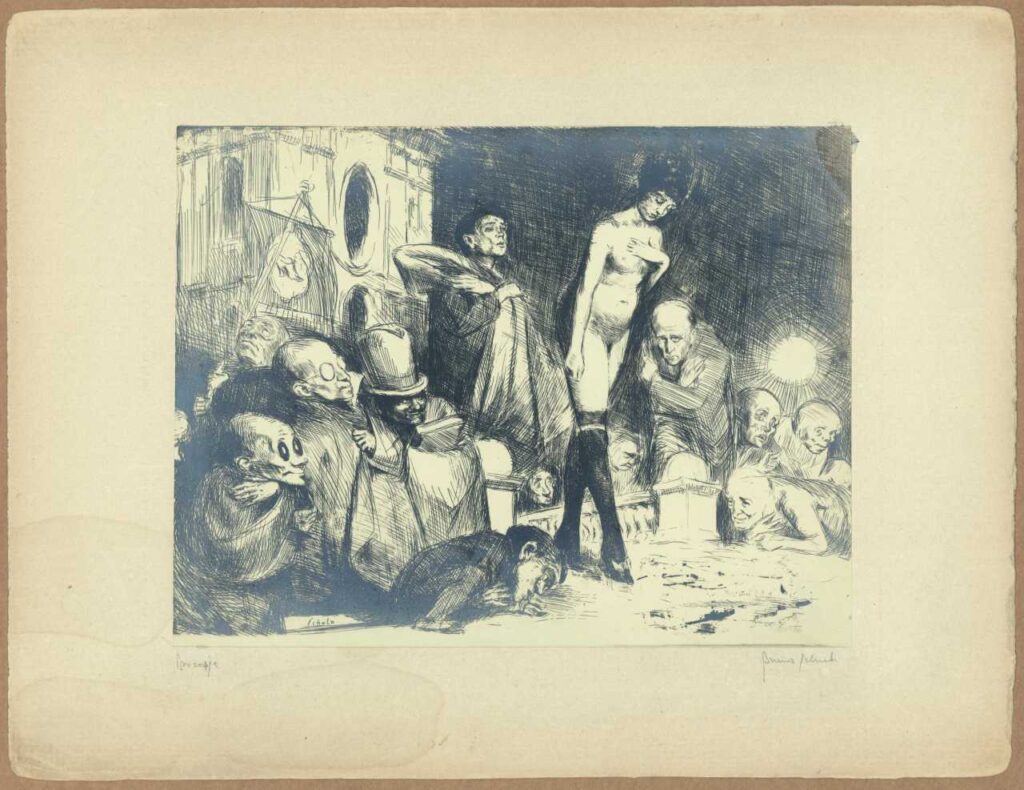

From the collection of The Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature in Warsaw

From the collection of The Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature in Warsaw

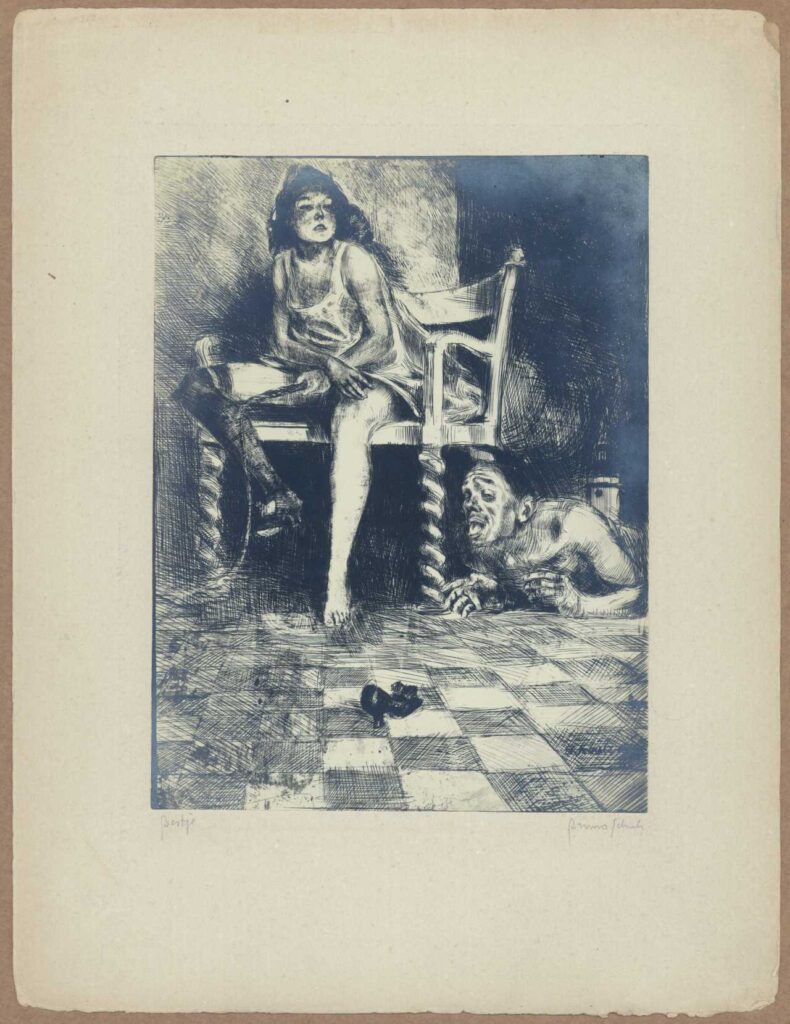

From the collection of The Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature in Warsaw

From the collection of The Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature in Warsaw

From the collection of The Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature in Warsaw

Spring, XIV

Translated into English by Celina Wieniewska

A band is now playing every evening in the city park, and people on their spring outings fill the avenues. They walk up and down, pass one another, and meet again in symmetrical, continuously repeated patterns. The young men are wearing new spring hats and nonchalantly carrying gloves in their hands. Through the hedges and between the tree trunks the dresses of girls walking in parallel avenues glow. The girls walk in pairs, swinging their hips, strutting like swans under the foam of their ribbons and flounces; sometimes they land on garden seats as if tired by the idle parade, and the bells of their flowered muslin skirts expand on the seats, like roses beginning to shed their petals. And then they disclose their crossed legs – white irresistibly expressive shapes – and the young men, passing them, grow speechless and pale, hit by the accuracy of the argument, completely convinced and conquered.

At a particular moment before dusk all the colors of the world become more beautiful than ever, festive, ardent yet sad. The park quickly fills with pink varnish, with shining lacquer that makes every other color glow deeper; and at the same time the beauty of the colors becomes too glaring and somewhat suspect. In another instant the thickets of the park strewn with young greenery, still naked and twiggy, fill with the pinkness of dusk, shot with coolness, spilling the indescribable sadness of things supremely beautiful but mortal.

Then the whole park becomes an enormous, silent orchestra, solemn and composed, waiting under the raised baton of the conductor for its music to ripen and rise; and over that potential, earnest symphony a quick theatrical dusk spreads suddenly as if brought down by the sounds swelling in the instruments. Above, the young greenness of the leaves is pierced by the tones of an invisible oriole, and once everything turns somber, lonely, and late, like an evening forest.

A hardly perceptible breeze sails through the treetops, from which dry petals of cherry blossom fall in a shower. A tart scent drifts high under the dusky sky and floats like a premonition of death, and the first stars shed their tears like lilac blooms picked from pale, purple bushes.

It is then that a strange desperation grips the youths and young girls walking up and down and meeting at regular intervals. Each man transcends himself, becomes handsome and irresistible like a Don Juan, and his eyes express a murderous strength that chills a woman’s heart. The girls’ eyes sink deeper and reveal dark labyrinthine pools. Their pupils distend, open without resistance, and admit those conquerors who stare into their opaque darkness. Hidden paths of the park reveal themselves and lead to thickets, ever deeper and more rustling, in which they lose themselves, as in a backstage tangle of velvet curtains and secluded corners. And no one knows how they reach, through the coolness of these completely forgotten darkened gardens, the strange spots where darkness ferments and degenerates, and vegetation emits a smell like the sediment in long-forgotten wine barrels.

Wandering blindly in the dark plush of the gardens, the young people meet at last in an empty clearing, under the last purple glow of the setting sun, over a pond that has been growing muddy for years; on a rotting balustrade, somewhere at the back gate of the world, they find themselves again in pre-existence, a life long past, in attitudes of a distant age; they sob and plead, rise to promises never to be fulfilled, and, climbing up the steps of exaltation, reach summits and climaxes beyond which there is only death and numbness of nameless delight.